- Journal of Inorganic Materials

- Vol. 36, Issue 5, 552 (2021)

Abstract

As the main inorganic component in human bone and tooth, hydroxyapatite (HA) presents good biocompatibility and bioactivity, and has been widely used for biomedical applications, especially in the orthopedic field[

To the best of our knowledge, the properties of the precursor powder and sintering processes are two key factors to affect the performances of the resulting ceramics. Up to now, many sintering techniques have been developed to fabricate HA nanoceramics, such as spark plasma sintering[

The present study attempted to construct HA nanoceramics with high mechanical strength by optimizing the initial powder, and investigated their efficiency in cellular viability. Firstly, three different HA precursor powders were synthesized, and their morphologies, size distributions, crystallinities, and specific surface areas were characterized. Then, the surface topography, phase composition, surface wettability, and mechanical strength of the resulting ceramics were investigated. Finally, the in vitro cell co-culturing with HA nanoceramics were performed to evaluate their cellular viability.

1 Materials and methods

1.1 Material preparation

HA precursor powders were prepared by wet chemical precipitation method as mentioned before[

1.2 Material characterization

The morphologies of the HA precursor powders and resulting ceramics were observed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S-4800N, Hitachi, Japan). The phase composition and crystal structure of the samples were analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD, Philips χ’Pert 1 X-ray diffractometer, Netherlands), where the measured angle was collected from 20° to 60° at a step size of 0.02°. The crystallinity (Xc) of the samples were calculated by the following equation:

Where I300 represents the intensity of (300) diffraction peak, V112/300 is the intensity of the hollow between (112) and (300) reflections[

The chemical groups of the samples were analyzed using a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FT-IR, Nicolet 6700, Thermo, USA). Infrared spectra of the HA precursor powders were used to assess the crystallinity index of the samples, which was calculated as the sum of the peak intensities at 602 and 563 cm-1 divided by the valley intensity between the two peaks[

1.3 In vitro cell study

Murine MC3T3-E1 pre-osteoblasts were selected as model to co-culture with the resulting HA ceramics, according to the previously reported procedures[

1.4 Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance by SPSS 11.0 software (SPSS Inc., USA) was used to perform the statistical analysis of the data. All of the quantitative results were obtained from at least triplicate measurements, and the data were all expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

2 Results

2.1 Characteristics of the HA initial powder

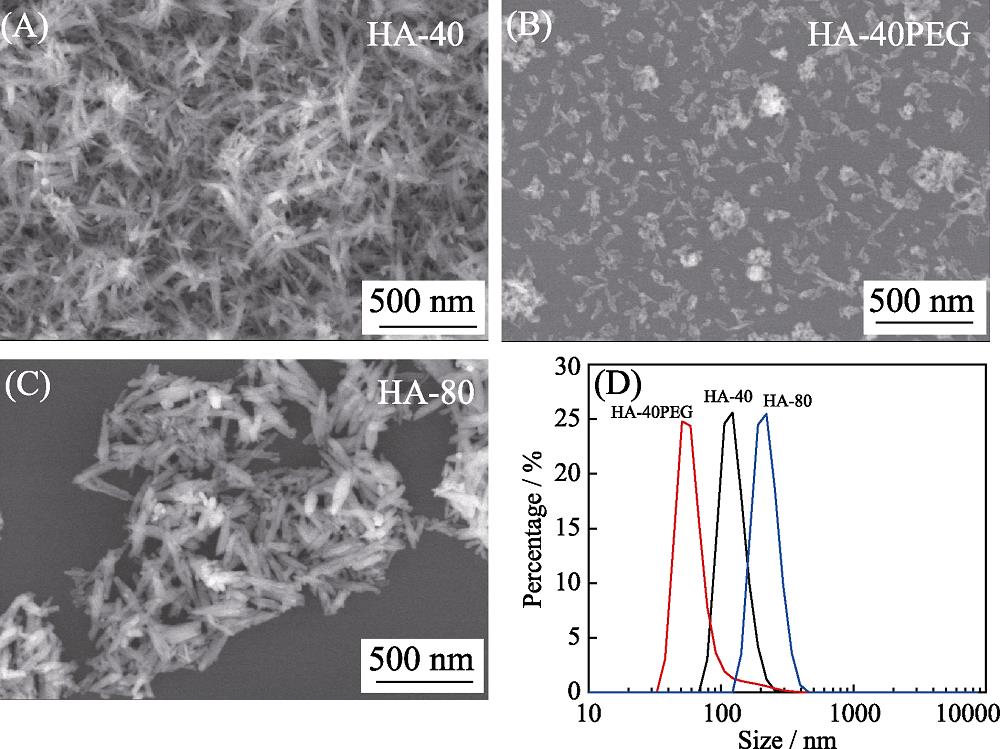

Fig. 1 shows the morphologies and phase compositions of various HA precursor powders. The crystals of both HA-40 (Fig. 1(A)) and HA-80 (Fig. 1(C)) presented the needle-like morphology, and the obvious agglomeration among the crystals could be observed. With the addition of PEG, the dispersity of the HA-40PEG powders was improved significantly (Fig. 1(B)). Compared with HA-40 and HA-80, HA-40PEG exhibited smaller crystal size. This was also verified by the particle size distribution tests (Fig. 1(D)). All of the three powders had narrow particle size distributions. Their D50 values were (124.62± 28.71), (65.16±31.23) and (221.50±48.82) nm, respectively. Specific surface areas of HA-40, HA-40PEG, and HA-80 were (89.76±3.96), (81.40±0.66), and (41.76±0.71) m2·g-1, respectively (Table 1).

![]()

Figure 1.(A-C) SEM images and (D) particle size distributions of various HA precursor powders

| Sample | Particle size, D50/nm | Crystallinity, Xc/% | Specific surface area/(m2·g-1) | Crystallinity index | Maturity index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA-40 | (124.62±28.71) | 31.76 | (89.76±3.96) | 5.91 | 2.02 |

| HA-40PEG | (65.16±31.23) | 39.48 | (81.40±0.66) | 5.31 | 1.91 |

| HA-80 | (221.50±48.82) | 77.94 | (41.76±0.71) | 7.45 | 1.86 |

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of the three HA precursor powders

Fig. 2(A) shows XRD patterns of three HA precursor powders. The diffraction peaks of each powder were well in line with those of HA standard (JCPDS 09-0432), indicating that they were composed of pure HA phase. Their crystallinities were also calculated and listed in Table 1. It could be observed that the crystallinity of powder synthesized at 80 ℃ was the highest (77.94%), followed by the powder of HA-40PEG (39.48%). The powder synthesized at 40 ℃ showed the lowest crystallinity of 31.76%. In addition, three kinds of powders exhibited similar FT-IR spectra (Fig. 2(B)). The bands at 602 and 563 cm-1 were assigned to the P-O bending mode (ν4), 1090 and 1037 cm-1 to asymmetric stretching mode (ν3), and 962 cm-1 to symmetric stretching vibration (ν1). The O-H group stretching and vibrational bands at 3570 and 629 cm-1. No characteristic PEG peaks were found in HA-40PEG, indicating that the PEG had been washed out from the HA powders. The crystallinity index of each HA precursor powder is shown in Table 1. The crystallinity indexes of the powders HA-40, HA-40PEG and HA-80 were 5.91, 5.31, and 7.45, respectively. In general, the higher crystallinity index is, the larger and/or more ordered crystals are[

![]()

Figure 2.(A) XRD patterns and (B) FT-IR spectra of HA initial powder (HA-40, HA-40PEG, HA-80)

2.2 Microstructures of HA ceramics

Fig. 3(A) shows the SEM images of the obtained ceramics of HA-40, HA-40PEG and HA-80. All of the samples exhibited the typically ceramic morphology that obvious grain boundaries distributed among the ceramic grains. The grain size of HA-80 ((316.65±68.91) nm, analyzed by Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software, Fig. 3(B)) was larger than that of HA-40 ((217.87±57.53) nm), indicating that the lower crystallinity of the powder might result in the HA ceramics with smaller grain size. Furthermore, the grain size of HA-40PEG was at nano-scale level ((123.22± 20.16) nm), the nanocrystalline might exert great influence on the property of the resulting HA ceramic. The XRD patterns (Fig. 3(C)) indicated that HA-40, HA-40PEG and HA-80 were all composed of HA phase, and all of the three kinds of HA ceramics had relatively high crystallinity (>96%, listed in Table 2) by calculation. These results indicated that the HA initial powder synthesized with the addition of PEG and relatively low temperature was beneficial to the fabrication of HA nanoceramics.

![]()

Figure 3.(A) SEM images, (B) average grain sizes and (C) XRD patterns of the three kinds of HA ceramics (HA-40, HA-40PEG and HA-80)

| Sample | Crystallinity, Xc/% | Surface roughness, Ra/nm | Contact angle/(°) | Grain size/nm | Relative density/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA-40 | 97.48 | (61.49±5.65) | (69.20±6.94) | (217.87±57.53) | (94.90±2.27) |

| HA-40PEG | 96.92 | (66.70±2.81) | (56.07±0.42) | (123.22±20.16) | (93.45±3.32) |

| HA-80 | 98.33 | (57.81±3.44) | (79.83±1.99) | (316.65±68.91) | (85.57±0.91) |

Table 2.

Physicochemical properties of the three HA ceramics

2.3 Surface property of HA ceramics

AFM images of the three HA ceramics are shown in Fig. 4(A). It could be observed that the surface topographies of HA-40 and HA-80 were relatively smoother than that of HA-40PEG. From the line profiles shown in Fig. 4(B), HA ceramics with nanocrystalline (HA-40PEG) exhibited larger fluctuation of surface morphology than the other two groups. The value of surface roughness was also calculated and list in Table 2. HA-40PEG with nanocrystalline had higher surface roughness (Ra, (66.70± 2.81) nm) than HA-40 ((61.49±5.65) nm) and HA-80 ((57.81±3.44) nm). The contact angles of the HA ceramics are showed in Fig. 4(C). They were in the order of HA-40PEG (56.07°±0.42°)

![]()

Figure 4.(A) AFM topographies, (B) line profiles, (C) contact angles of the three kinds of HA ceramics (HA-40, HA-40PEG and HA-80)

2.4 Mechanical strength of HA ceramics

The mechanical strengths of HA ceramics mainly depended on their microstructure, such as grain size, densities, and so on. As shown in Fig. 5(A), HA-40 and HA-40PEG had higher relative densities (~95%) than HA-80 (~85%), suggesting that the precursor powders synthesized at lower temperature was beneficial to obtain HA ceramics with higher density. All of the three kinds of HA ceramics exhibited typically brittle fracture from their strain-stress curves (Fig. 5(B)). HA-40PEG possessed higher compressive strength (Fig. 5(C)) and elastic modulus (Fig. 5(D)) than HA-40 and HA-80. The relatively high mechanical properties of HA-40PEG might be partly attributed to its small grain size and high density.

![]()

Figure 5.(A) Relative densities, (B) strain-stress curves, (C) compressive strengths and (D) elastic modulus of the three kinds of HA ceramics (HA-40, HA-40PEG and HA-80)Values are expressed as the mean ± SD (

2.5 Cell spreading and proliferation

An excellent biomaterial should be also beneficial for cell adhesion and growth. After for 2 d of culturing, MC3T3-E1 exhibited a typical spindle-like morphology with outstretched filopodia to tightly grasp the ceramic grains from SEM images (Fig. 6(A)). As compared to HA-40 and HA-80, more filopodia were found in cells grown on HA-40PEG with nanocrystalline.

![]()

Figure 6.(A) SEM images, (B) CLSM observations of cytoskeleton, (C) cell area, and (D) CCK-8 results of MC3T3-E1 cultured on HA ceramicsValues are expressed as the mean ± SD (

Quantitative analysis of cell morphology showed that cells attached on HA-40PEG had significantly larger cell area than those on HA-40 and HA-80 (Fig. 6(C)). The morphology of MC3T3-E1 grown on three kinds of HA ceramics was further stained with TRITC conjugated- phalloidin for cytoskeleton and observed by CLSM (Fig. 6(B)). The cells displayed elongated flatten morphology and began to contact with each other at 3 d. CCK-8 results (Fig. 6(D)) indicated that obvious cell proliferation was observed on three kinds of HA ceramics, and the cell viabilities on HA-40 and HA-40PEG were higher than HA-80 at 5 d. These results suggested that HA with nanocrystalline was beneficial to the spreading and proliferation of MC3T3-E1.

3 Discussion

It is still a hot topic to seek a balance between the simultaneous enhancements of mechanical strength and biological property in HA ceramics. Construction of nanoceramics may be an effective way to solve this problem. In the previous studies, the nanoceramics exhibited the higher mechanical properties in compress strength, fracture toughness and hardness than microceramics[

In this study, three kinds of HA precursor powders were firstly synthesized at different temperatures and with PEG addition by employing wet chemical precipitation method. Comparing with HA-40 and HA-80, HA-40PEG synthesized at low temperature (40 ℃) with PEG addition owned smaller grain size, which contributed to the densification of the resulting ceramic in the sintering process. And the powder with low crystallinity and high specific surface area was suitable for the fabrication of HA nanoceramics[

The mechanical strength of HA ceramics was mainly influenced by their compactness and grain size. When the grain size decreased to nanoscale, the number of grain boundaries and the crack deflections increased (from transgranular fracture to intergranular fracture). Therefore, the nanoceramics can offer more resistance to crack propagation and dislocation motion, and exhibit higher compressive strength and elastic modulus than the submicro ones[

The surface morphology, surface roughness and hydrophilicity are important properties to biomaterials. The grain size of a material would influence the surface properties, such as surface area, charge and topography[

The relatively high surface roughness and hydrophilicity of HA-40PEG with nanocrystalline would have beneficial effects on the improvement of the bioactivity. When the grain size of HA ceramics decreased from micro-scale to nano-scale, cell adhesion mainly depended on the topography of the nanoceramics rather than surface chemistry[

4 Conclusions

Overall, the present study focused on the construction of HA nanoceramics by optimizing the precursor powders, and investigated their mechanical strengths and biological properties. The addition of PEG and relatively low reaction temperature were beneficial to obtain HA powders with small grain size and well dispersity, which was suitable for the fabrication of HA nanoceramics with high density and enhanced mechanical property. Because of the nanotopography, HA-40PEG exhibited relatively higher surface roughness and better hydrophilicity than the submicro ceramics, which promoted the cell adhesion and spreading. These findings highlight that the optimization of the precursor powder plays an important role in the fabrication of HA nanoceramics, which has a certain guiding significance for preparing HA bioceramics with simultaneous enhancement of mechanical strength and bioactivity.

References

[1] Y HONG, H FAN, B LI et al. Fabrication, biological effects, and medical applications of calcium phosphate nanoceramics. Materials Science & Engineering R, 70, 225-242(2010).

[2] S V DOROZHKIN. Calcium orthophosphates in nature. Biology and Medicine Materials, 2, 399-498(2009).

[3] B NASIRI-TABRIZI, P HONARMANDI, R EBRAHIMI-KAHRIZSANGI et al. Synthesis of nanosize single-crystal hydroxyapatite

[6] Z FANG, Q FENG, R TAN.

[7] O PROKOPIEV, I SEVOSTIANOV. Dependence of the mechanical properties of sintered hydroxyapatite on the sintering temperature. Materials Science & Engineering A, 431, 218-227(2006).

[10] R W RICE, C C WU, F BOICHELT. Hardness-grain-size relations in ceramics. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 77, 2539-2553(1994).

[11] B M MOSHTAGHIOUN, D GOMEZ-GARCIA, RODRIGUEZ A DOMINGUEZ- et al. Grain size dependence of hardness and fracture toughness in pure near fully-dense boron carbide ceramics. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 36, 1829-1834(2016).

[13] B N KIM, E PRAJATELISTIA, Y H HAN et al. Transparent hydroxyapatite ceramics consolidated by spark plasma sintering. Scripta Materialia, 69, 366-369(2013).

[14] X GUO, P XIAO, L JING et al. Fabrication of nanostructured hydroxyapatite

[15] S RAMESH, C Y TAN, S B BHADURI et al. Rapid densification of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite for biomedical applications. Ceramics International, 33, 1363-1367(2007).

[16] D VELJOVIC, B JOKIC, R PETROVIĆ et al. Processing of dense nanostructured HAP ceramics by sintering and hot pressing. Ceramics International, 35, 1407-1413(2009).

[17] J WANG, L L SHAW. Transparent nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite by pressure-assisted sintering. Scripta Materialia, 63, 593-596(2010).

[19] K LIN, L CHEN, J CHANG. Fabrication of dense hydroxyapatite nanobioceramics with enhanced mechanical properties

[20] M J LUKIĆ, S D ŠKAPIN, S MARKOVIĆ et al. Processing route to fully dense nanostructured HAp bioceramics: from powder synthesis to sintering. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 95, 3394-3402(2012).

[21] A THUAULT, E SAVARY, J C HORNEZ et al. Improvement of the hydroxyapatite mechanical properties by direct microwave sintering in single mode cavity. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 34, 1865-1871(2014).

[23] D LIU, Y WU, H WU et al. Effect of process parameters on the microstructure and property of hydroxyapatite precursor powders and resultant sintered bodies. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology, 16, 444-454(2018).

[24] J SONG, L YONG, Z YING et al. Mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite ceramics sintered from powders with different morphologies. Materials Science & Engineering A, 528, 5421-5427(2011).

[25] E LANDI, A TAMPIERI, G CELOTTI et al. Densification behaviour and mechanisms of synthetic hydroxyapatites. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 20, 2377-2387(2000).

[26] S WEINER, O BAR-YOSEF. States of preservation of bones from prehistoric sites in the Near East: a survey. Journal of Archaeological Science, 17, 187-196(1990).

[29] M MAZAHERI, M HAGHIGHATZADEH, A M ZAHEDI et al. Effect of a novel sintering process on mechanical properties of hydroxyapatite ceramics. Journal of Alloys & Compounds, 471, 180-184(2009).

[31] Y X PANG, X BAO. Influence of temperature, ripening time and calcination on the morphology and crystallinity of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 23, 1697-1704(2003).

[33] Y H TSENG, C S KUO, Y Y LI et al. Polymer-assisted synthesis of hydroxyapatite nanoparticle. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 29, 819-822(2009).

[34] H LI, F XUE, X WAN et al. Polyethylene glycol-assisted preparation of beta-tricalcium phosphate by direct precipitation method. Powder Technology, 301, 255-260(2016).

[35] M AKAO, H AOKI, K KATO. Mechanical properties of sintered hydroxyapatite for prosthetic applications. Journal of Materials Science, 16, 809-812(1981).

[36] B ARIFVIANTO, M MAHARDIKA, P DEWO et al. Effect of surface mechanical attrition treatment (SMAT) on microhardness, surface roughness and wettability of AISI 316L. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 125, 418-426(2011).

[41] C YAO, V PERLA, J L MCKENZIE et al. Anodized Ti and Ti6Al4V possessing nanometer surface features enhances osteoblast adhesion. Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology, 1, 68-73(2005).

Set citation alerts for the article

Please enter your email address