- Opto-Electronic Advances

- Vol. 7, Issue 12, 240122 (2024)

Abstract

Introduction

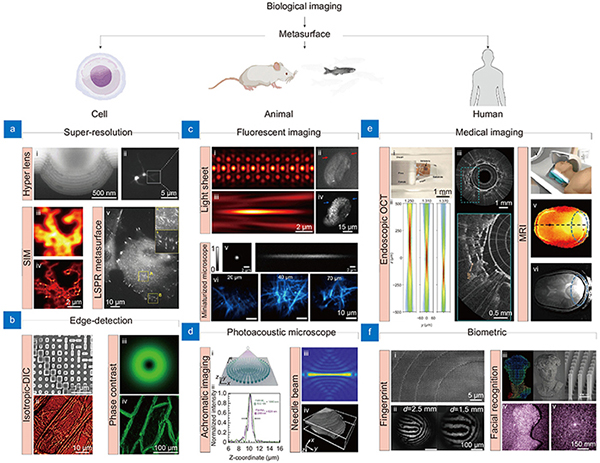

Biological imaging techniques are indispensable for the exploration of biological processes, structures, and states. Advanced imaging techniques have been widely studied for various biological applications, such as diagnosis, biometrics, and fundamental biological research. As the importance of biological imaging has been highlighted, there has been an increased demand for advanced imaging techniques that are faster, wider, clearer, and more accurate. However, enhanced performance is inevitably accompanied by increased system complexity, resulting in limited system performance. Many efforts have been made to reduce the system complexity by utilizing versatile and compact components that serve multiple functions, thereby creating a compressed optical system

Metasurfaces, consisting of regularly aligned nanostructures, are considered promising optical components for imaging techniques. They can manipulate optical properties such as amplitude, phase, polarization, absorption, and reflection through the arrangement of subwavelength-sized meta-atoms

![]()

Figure 1.

Principle of electromagnetic phase modulation

The operating principle of a metasurface follows the generalized Snell's law

![]()

Figure 2.

To precisely refract the light path, it is necessary to carefully design the phase delay and transmission at each position on the metasurface. Designing a complex phase map capable of modulating light in the desired direction and intensity according to the generalized Snell’s law and diffraction optical theory enables the realization of diverse optical functionalities. In this section, we focus on the principles and design strategies for metasurfaces.

Propagation phase

Propagation phase modulation is an innovative method for manipulating the phase delay of electromagnetic waves propagating through meta-atoms. The propagation phase is the phase accumulated during the propagation of light within the material of the meta-atom, which depends on the physical parameters of the material and the wavelength. By altering the physical structure of the meta-atom, it is possible to control the 2π phase for the incident polarized light. The physical structure here refers to the shape or physical dimensions of the meta-atom (such as height, length, width).

Propagation phase metasurfaces can be classified into two theories: nano waveguides and medium equivalent refractive index. The approach based on the medium equivalent refractive index utilizes the variation in refractive index between two or more media, where typically one of the media is a high refractive index material. It is the same concept as the generally known effective refractive index, which explains the complex structure of the meta-atom as an effective medium. It refers to the effective refractive index that appears when a wave propagates through the composite structure, allowing control of the phase change of light propagated through the meta-atom. This is used to describe the property of the meta-atom acting as an effective medium. Propagation phase modulation involves using meta-atoms as nano waveguides, where the phase delay is influenced by the effective refractive index and the dimensions of the meta-atom. More detailed discussion on how it act

The relationship between the incident and transmitted electric fields can be expressed using the Jones matrix [

where

Geometric phase

The geometric phase

The Jones matrix of rotated meta-atom can be expressed using the rotation matrix

Practically, designing a metasurface using linearly polarized light is inconvenient because the metasurface must be precisely aligned in the polarization direction. Because of this alignment issue, circularly polarized light is commonly adopted for designing PB-phase metasurface. The transmission matrix of the linear polarization basis can be converted to that of the circular polarization basis using conversion matrix

where, the subscripts R and L in

According to

Geometric phase metasurfaces effectively utilize their degrees of freedom to manipulate various electromagnetic events, including unusual refraction or diffraction

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the meta-atoms in the propagation and geometric phases are shown in

Optimization of unit cell period

The periodicity of the meta-atom is one of a key design factor. If the periodicity is too large or small, unwanted coupling between meta-atoms may occur, owing to the emergence of additional propagation modes and the occurrence of higher-order diffraction orders [

where,

Additionally, the

Dispersion modulation

The dispersion is the deviation of light from the original path in a wavelength-dependent manner as it passes through a dispersive medium. The dispersion modulation is a common issue in the field of metasurfaces for wavelength dependent designing, such as achromatic metasurfaces

The sophisticated engineering of group delay (GD) and group delay dispersion (GDD) is being revisited as an effective solution for controlling the dispersion

where

where

Materials for metasurface

Proper selection of materials properly is critical for biological imaging in terms of imaging quality, fabrication and biocompatibility. The optical properties of materials, such as refractive index and optical extinction coefficient, greatly influence the phase design strategy and degree of freedom, as they govern the phase delay, transmission and polarization of matesurfaces in a wavelength dependent manner. The material should be compatible with nanofabrication for building meta-atoms. For biological applications, another crucial condition is biocompatibility. Metasurfaces that do not directly contact object being imaged are relatively free from biocompatibility concerns. However, in applications where direct contact occurs such as hyperlenses and local surface plasmonic resonance (LSPR), material selection should be carefully considered. It is worth noting that biocompatibility of designed metasurfaces should be tested before in vivo and in vitro applications since the biocompatibility depends not only on the materials, but also on the structure, size and species of subject. For example, although gold is widely known for its biocompatibility and used in plasmonic applications, gold nanoparticles can exhibit cytotoxic effect at certain sizes and concentrations

Plasmonic material

Surface plasmons (SPs)

Plasmonic resonators can control the phase, amplitude, polarization, and dispersion of light by adjusting the material properties, geometry, and vibrational frequency. Surface plasmonic resonators (SPR) have been adopted as unit cells for metasurfaces owing to their versatility. However, SPR has limitations arising from a phenomenon known as momentum mismatch

![]()

Figure 3.

Another promising plasmonic resonator is the gap surface plasmonic resonator (GSPR)

Although GSPR achieves high reflection efficiency, reducing optical loss remains a challenge in the design of highly efficient metasurfaces. This loss is particularly critical for visible light and communication wavelengths. Commonly used plasmonic materials such as gold and silver have limitations in the visible range owing to the inherent loss of metals and heat dissipation

Dielectric material

Owing to their low efficiency and high intrinsic ohmic loss

Dielectric meta-atoms with high refractive indices can effectively couple with various multipolar modes of Mie resonances

Dielectric materials with high refractive indices can effectively refract and confine light, functioning as waveguide modes that facilitate enhanced light-matter interactions. Operating as waveguide elements allows them to work over a broad bandwidth, demonstrating high transmittance and complete phase modulation. The energy of the incident light wave, which is limited inside the meta-atom, delays the propagation phase of the light, enabling phase accumulation

where,

The fill factor (FF), signifying the ratio of space filled by specific elements within a structure, allows for the manipulation of the phase shift

Tunable material

Light modulation is sometimes required during optical imaging in various purposes, such as switching between different imaging modes. Generally, spatial light modulator (SLM) has been employed for these purposes, but it is associated with drawbacks including high cost, complicated system requiring maintenance, and limited diffraction angles due to the large pixel sizes. As an alternative or complement, tunable matasurfaces are being explored for specific applications. Selecting appropriate materials with optical properties that can be modulated by external stimuli, such as electric fields or temperature, is crucial for implementing these devices. In this section, we will briefly discuss representative materials widely used for creating tunable metasurfaces.

One popular class is phase change materials (PCMs), which undergo transitions between states (e.g., amorphous and crystalline) depending on the external conditions, resulting in the significant change of optical properties. Chalcogenide compounds such as Ge2Sb2Te5 (GST)

Liquid crystal (LC)

Applications

To acquire high-quality images from biological samples, several parameters of optical system should be optimized, such as NA, field of view (FOV), depth of field (DOF), achromaticity, and imaging time. These parameters should be carefully tuned depending on the imaging modalities to build a high-performance optical system since they trade off against each other and typically cannot be optimized simultaneously. For example, while utilizing high NA metasurfaces enables high-resolution imaging, it reduces the FOV and DOF, restricting the large-field 3D bioimaging. Thus, many kinds of optimization techniques have been adopted to find optimal metasurfaces for bioimaging

The point spread function (PSF) engineering could be a good solution for optimizing the system for microscopic imaging. It is particularly worth noting the utilization of non-diffracting light, which preserves the size and intensity profile during propagation, in the field of bioimaging

Metasurfaces for cell imaging applications

Owing to its simplicity, cells have been used as a basic object for imaging in the field of biology. They are often used in a wide range of biological studies such as clinics, diagnostics, and drug screening. Due to their importance, a lot of imaging techniques adapted for cell imaging have been developed. In this section, various metasurfaces for advanced cell imaging techniques are discussed.

Super-resolution imaging

The optical resolution is defined as the minimum distinguishable distance between two points and is determined by the NA and wavelength of the optical systems. Even when enhanced using high-NA optics or short wavelengths, the resolution does not improve beyond a certain level (~250 nm) at visible wavelengths owing to the physical limit of diffraction, known as the ‘diffraction limit’

To achieve diffraction-unlimited resolution, the behavior of wave propagation should be considered. According to angular spectrum theory, waves are categorized into propagating and non-propagating waves, termed evanescent waves. Evanescent waves are exponentially decaying waves near a light source that convey structural information smaller than its wavelength

The initial versions of hyperlenses

![]()

Figure 4.

Metasurfaces also can be used for SIM, which achieves super-resolution by combining images illuminated by several patterns. The maximally achievable spatial frequency of conventional SIM is determined by the sum of the illumination and detection spatial frequencies

Typically, the metasurfaces for super-resolution imaging based on near field approaches suffer from optical loss and sample mounting

By sophisticated design, practical SOL metasurfaces have been fabricated by patterning a periodically aligned concentric nanostructure

Edge-detection metasurface

In the field of bioimaging, computational image processing has become indispensable for advancing optical imaging techniques. However, these techniques often require significant computational resources and processing time, which prohibit the real-time monitoring of biological activities. A promising solution to alleviate this burden is to employ an special optical elements for all-optical analog image processing, similar to hardware acceleration in the field of electronics

![]()

Figure 5.

Second-order spatial differentiation is a sophisticated mathematical procedure employed to ascertain the rate of change in the spatial gradient of a function

Edge-detection can also be implemented using spiral phase metasurfaces that incorporate a hyperbolic phase with a topological charge of 1

One promising approach for edge detection is nonlocal metasurface, which manipulate light in momentum domain. The term “nonlocal” indicates that meta-atoms of the metasurface interacts with the incident light in a collective manner rather individual elements

Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy is another example of label-free imaging of transparent samples

Tunable metasurfaces

Correlative imaging across various imaging modalities (i.e., combining bright field and edge-detection mode) is often required to unveil complex biological processes. However, complexity of optical setup restricts the implementation of combining different imaging modalities. Thus, tunable optics are preferred for constructing correlative imaging systems, as they can minimize the physical vibration and perturbations during mode switching. Metasurfaces also have emerged as strong candidates for tunable imaging system owing to their thin nature and abundant design flexibility. Switching modes of metasurfaces can be achieved in several ways, including electrical, mechanical (e.g., stretching), and stimuli-responsive (e.g., thermal) methods. In this section, tunable metasurfaces are comprehensively discussed.

Liquid crystal (LC) cell is the most representative tools for realization of electrically tunable metasurfaces. Their anisotropic refractive index and responsiveness to electric fields enable effective modulation of optical phases

![]()

Figure 6.

Metasurfaces for tissue and animal imaging applications

Optical microscopy is an indispensable tool for imaging biological sampels

Although these techniques exhibit superior performance, they require expensive and bulky hardware and careful maintenance. Integrating multiple functions into a limited space requires considerable cost and effort to precisely maintain and align the systems. Metasurfaces have received increasing attention as alternative solutions to address these issues. The multifunctionality and thin nature of metasurfaces enable the combination of multiple optical elements into a single flat component, resulting in significant system simplification. In this section, conventional optical imaging methods specialized for animal and tissue imaging are introduced and explored to understand their potential replacement by metalsurfaces.

Fluorescent microscopy

As the demand for fast and large-field imaging has increased in the field of biology, various types of advanced fluorescent microscopies are under development. Among them, light-sheet microscopy is particularly promising owing to its efficiency and fast imaging speed

![]()

Figure 7.

Another important microscopic technique in the biological field is multiphoton microscopy for deep-tissue imaging using a femtosecond laser in the near-infrared range. However, designing a metasurfaces for multiphoton fluorescence microscopy is challenging because of the larger difference between the excitation and emission wavelengths compared with single-photon microscopy. By utilizing the multifunctionality of metasurfaces, Arbabi et al.

Fluorescence is the process of emitting light with a longer wavelength after absorbing light with a shorter wavelength and is known as the Stokes shift. Because of its broadband spectrum, fluorescence imaging typically involves optical components designed for wide spectrum. While currently available conventional achromatic lenses exhibit superior performance in correcting chromatic aberrations, compensating for chromatic aberrations remains a challenge for metasurfaces

Photoacoustic microscopy (PAM)

Photoacoustic microscopy (PAM) is an innovative imaging approach, overcoming the limitation of the penetration depth of light in scattering media by harnessing acoustic signals

Extending DOF significantly increases the clear imaging volume, as the PAM acquires an ultrasound signal in the vertical direction. Although Bessel beams are commonly employed to increase the DOF, their low efficiency and the need for additional optical elements are obstacles to high-quality imaging. Song et al.

![]()

Figure 8.

Metasurfaces for human applications

This chapter discusses innovative idea of metasurfaces for human applications. From medical devices and biometrics, metasurfaces have enhanced the resolution, sensitivity, and diversity of devices for human applications, such as endoscopic imaging, MRI, 3D facial recognition and fingerprint imaging. This chapter explores into the innovative potential of metasurfaces on devices for human applications.

Endoscopic imaging

Endoscopy is an optical imaging technique used to visually inspect internal organs. This technology has become an essential tool for acquiring minimally invasive organ images, particularly by using high-resolution fiber-optic systems

Pahlevaninezhad et al.

![]()

Figure 9.

As mentioned previously, the ability of metasurfaces to control the properties of light enables more accurate diagnostics that are not possible using traditional fiber-optic catheters. Endoscopic imaging using a metasurface, which is sensitive to polarization, allows for a clearer distinction of the surrounding tissues compared to traditional fiber-optic endoscopes

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI is an advanced medical imaging technology that has evolved over nearly 50 years and can visualize a wide range of anatomical structures such as the brain, spine, muscles, joints, organs, and blood vessels. It offers exceptional contrast for soft tissues, enabling the diagnosis of neurological disorders, musculoskeletal conditions, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer

The use of metasurfaces has been proposed as a solution to enhance MRI resolution without a stronger magnetic field. A metasurface can resonantly enhance the strength of a magnetic field and spatially redistribute it by increasing the coupling between radio-frequency coils in specific areas

Schmidt et al.

Devices for facial recognition

Traditional facial recognition has been studied for auxiliary communication, mental health and emotion monitoring, pain assessment, and the interpretation of facial nuances

Metasurfaces are considered promising components for dot projection-based 3D depth encoding devices owing to their simplicity and ability to generate an enormous number of point clouds

![]()

Figure 10.

Structured light-based facial depth encoding techniques have been adopted in smartphones for device unlocking and biometric payment systems. Conventional facial recognition modules often employ vertical cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSEL) as structured light sources owing to their low power consumption. The integration of metasurfaces with VCSEL has been proposed for more power-efficient and arbitrary light modulation

Devices for fingerprint recognition

Biometric fingerprint recognition is a robust security mechanism that utilizes the unique fingerprint patterns of individuals for identity verification. The journey of fingerprint recognition commenced in England in 1684, when Grew discovered the uniqueness of people's fingerprints

Recently, there has been an increasing demand for fingerprint recognition, particularly for its integration into handheld devices such as smartphones, driving continuous advancements in technology. To satisfy these increasing demands, the use of metasurfaces has led to significant advancements over traditional methods. This enables the creation of compact, high-resolution, and sensitive optical systems, significantly enhancing their applicability in security and personal authentication. Metasurfaces are particularly suitable for large-field imaging over short distances, such as fingerprint imaging. Quadratic phase metasurface imaging systems, with their wide FOV (~100°) and ability to capture the fine patterns with high precision (~100 µm), can offer a compact and reliable method of fingerprint authentication [

Conclusions and future perspectives

In this review, we have explored the principles of metasurface design and its comprehensive applications in the field of biological imaging. The remarkable features of metasurface, such as their multifunctionality, thinness, and compatibility with conventional optical systems, render them promising optical elements. Particularly in bioimaging, their potential to replace bulky and complex components with simpler, more efficient ones is noteworthy. To comprehensively cover the metasurfaces from basic principles to applications, we first discussed the principes of phase modulation of metasurfaces. Then, we have explored the representative classes of materials for creating metasurfaces depending on their properties. Particularly, dielectric materials and tunable materials are most widely used for bioimaging due to its compatibility within visible range and versatility. Furthermore, we showcased the broad applications of metasurface in biological field depending on the subject, such as cell, tissue, and human. The detailed categories include promising techniques for bioimaging, such as super-resolution

Although metasurfaces appear to be promising tools, three major limitations and challenges need to be addressed for them to replace, or at least be used alongside, conventional optics. First, current metasurface-based imaging systems suffer from aberrations and efficiency issues. These problems degrade image quality and hinder the accurate collection of biological data. Additionally, the small metasurfaces require additional topcail system for magnification. Imaging through current metasurfaces has lower light efficiency and higher aberrations compared to traditional lenses. For instance, fluorescence imaging, which is gold-standard for bioimaging, requires a sensitive detection system due to its poor efficiency, and light collection efficiency of metasurfaces is not adequate. Efforts are being made to resolve these issues through computational methods. Recent image processing techniques based on deep learning offer impressive correcting performance. Additionally, advanced inverse design methods enables the development of high-efficiency metasurfaces

Despite these limitations, leveraging the advantages of metasurfaces can significantly enhance the performance in bioimaging, making them a promising technology. Among their various merits, we would like to highlight three key advantages of metasurface for bioimaging. First, metasurfaces are highly specialized for PSF engineering, which offers significant benefits for scanning type microscopes. If strong illumination, generally available for scanning type microscope, is given, it can compensate for the low efficiency of metasurfaces. Furthermore, data acquisition using scanning methods enlarges imaging field of view and reduces aberrations. Indeed, this is well demonstrated in previous studies such as PAM

Although still in the early stages, the integration of metasurfaces with biological imaging holds the potential to revolutionize the field. The synergy between metasurfaces and advanced imaging techniques promises to enhance the performance and capabilities of imaging systems, introducing novel functionalities that are unattainable with traditional optical components. In the future, we anticipate that metasurfaces will play a pivotal role in various imaging applications, including real-time diagnostics, high-resolution imaging, and non-invasive medical procedures. Continued research and development in optics, materials science, and image processing will expand the application boundaries of metasurfaces, establishing them as a cornerstone of next generation bioimaging technologies.

References

[1] I Avrutsky, K Chaganti, I Salakhutdinov et al. Concept of a miniature optical spectrometer using integrated optical and micro-optical components. Appl Opt, 45, 7811-7817(2006).

[2] M Khorasaninejad, F Capasso. Metalenses: versatile multifunctional photonic components. Science, 358, eaam8100(2017).

[3] M Khorasaninejad, WT Chen, RC Devlin et al. Metalenses at visible wavelengths: diffraction-limited focusing and subwavelength resolution imaging. Science, 352, 1190-1194(2016).

[4] XJ Ni, S Ishii, AV Kildishev et al. Ultra-thin, planar, Babinet-inverted plasmonic metalenses. Light Sci Appl, 2, e72(2013).

[5] I Kim, J Jang, G Kim et al. Pixelated bifunctional metasurface-driven dynamic vectorial holographic color prints for photonic security platform. Nat Commun, 12, 3614(2021).

[6] I Kim, WS Kim, K Kim et al. Holographic metasurface gas sensors for instantaneous visual alarms. Sci Adv, 7, eabe9943(2021).

[7] R Paniagua-Dominguez, YF Yu, E Khaidarov et al. A metalens with a near-unity numerical aperture. Nano Lett, 18, 2124-2132(2018).

[8] HW Liang, QL Lin, XS Xie et al. Ultrahigh numerical aperture metalens at visible wavelengths. Nano Lett, 18, 4460-4466(2018).

[9] H Chung, OD Miller. High-NA achromatic metalenses by inverse design. Opt Express, 28, 6945-6965(2020).

[10] SY Zhang, CL Wong, SW Zeng et al. Metasurfaces for biomedical applications: imaging and sensing from a nanophotonics perspective. Nanophotonics, 10, 259-293(2021).

[11] DD Nguyen, S Lee, I Kim. Recent advances in metaphotonic biosensors. Biosensors, 13, 631(2023).

[12] WT Chen, AY Zhu, V Sanjeev et al. A broadband achromatic metalens for focusing and imaging in the visible. Nat Nanotechnol, 13, 220-226(2018).

[13] RJ Lin, VC Su, SM Wang et al. Achromatic metalens array for full-colour light-field imaging. Nat Nanotechnol, 14, 227-231(2019).

[14] J Rho, ZL Ye, Y Xiong et al. Spherical hyperlens for two-dimensional sub-diffractional imaging at visible frequencies. Nat Commun, 1, 143(2010).

[15] D Lee, YD Kim, M Kim et al. Realization of wafer-scale hyperlens device for sub-diffractional biomolecular imaging. ACS Photonics, 5, 2549-2554(2018).

[16] YU Lee, JX Zhao, Q Ma et al. Metamaterial assisted illumination nanoscopy via random super-resolution speckles. Nat Commun, 12, 1559(2021).

[17] S Masuda, T Kuboki, S Kidoaki et al. High axial and lateral resolutions on self-assembled gold nanoparticle metasurfaces for live-cell imaging. ACS Appl Nano Mater, 3, 11135-11142(2020).

[18] PC Huo, C Zhang, WQ Zhu et al. Photonic spin-multiplexing metasurface for switchable spiral phase contrast imaging. Nano Lett, 20, 2791-2798(2020).

[19] XW Wang, H Wang, JL Wang et al. Single-shot isotropic differential interference contrast microscopy. Nat Commun, 14, 2063(2023).

[20] FH Shi, J Wen, DY Lei. High-efficiency, large-area lattice light-sheet generation by dielectric metasurfaces. Nanophotonics, 9, 4043-4051(2020).

[21] Y Luo, ML Tseng, S Vyas et al. Meta-lens light-sheet fluorescence microscopy for in vivo imaging. Nanophotonics, 11, 1949-1959(2022).

[22] CH Wang, QM Chen, HL Liu et al. Miniature two-photon microscopic imaging using dielectric metalens. Nano Lett, 23, 8256-8263(2023).

[23] A Barulin, H Park, B Park et al. Dual-wavelength UV-visible metalens for multispectral photoacoustic microscopy: a simulation study. Photoacoustics, 32, 100545(2023).

[24] W Song, CK Guo, YT Zhao et al. Ultraviolet metasurface-assisted photoacoustic microscopy with great enhancement in DOF for fast histology imaging. Photoacoustics, 32, 100525(2023).

[25] H Pahlevaninezhad, M Khorasaninejad, YW Huang et al. Nano-optic endoscope for high-resolution optical coherence tomography in vivo. Nat Photonics, 12, 540-547(2018).

[26] R Schmidt, A Slobozhanyuk, P Belov et al. Flexible and compact hybrid metasurfaces for enhanced ultra high field in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Sci Rep, 7, 1678(2017).

[27] E Lassalle, TWW Mass, D Eschimese et al. Imaging properties of large field-of-view quadratic metalenses and their applications to fingerprint detection. ACS Photonics, 8, 1457-1468(2021).

[28] WC Hsu, CH Chang, YH Hong et al. Metasurface- and PCSEL-based structured light for monocular depth perception and facial recognition. Nano Lett, 24, 1808-1815(2024).

[29] NF Yu, P Genevet, MA Kats et al. Light propagation with phase discontinuities: generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science, 334, 333-337(2011).

[30] J Hu, S Bandyopadhyay, YH Liu et al. A review on metasurface: from principle to smart metadevices. Front Phys, 8, 586087(2021).

[31] NF Yu, F Capasso. Flat optics with designer metasurfaces. Nat Mater, 13, 139-150(2014).

[32] M Khorasaninejad, AY Zhu, C Roques-Carmes et al. Polarization-insensitive metalenses at visible wavelengths. Nano Lett, 16, 7229-7234(2016).

[33] M Khorasaninejad, WT Chen, J Oh et al. Super-dispersive off-axis meta-lenses for compact high resolution spectroscopy. Nano Lett, 16, 3732-3737(2016).

[34] JPB Mueller, NA Rubin, RC Devlin et al. Metasurface polarization optics: independent phase control of arbitrary orthogonal states of polarization. Phys Rev Lett, 118, 113901(2017).

[35] LQ Cong, NN Xu, WL Zhang et al. Polarization control in terahertz metasurfaces with the lowest order rotational symmetry. Adv Opt Mater, 3, 1176-1183(2015).

[36] XZ Chen, LL Huang, H Mühlenbernd et al. Dual-polarity plasmonic metalens for visible light. Nat Commun, 3, 1198(2012).

[37] A Arbabi, Y Horie, M Bagheri et al. Dielectric metasurfaces for complete control of phase and polarization with subwavelength spatial resolution and high transmission. Nat Nanotechnol, 10, 937-943(2015).

[38] SC Jiang, X Xiong, YS Hu et al. High-efficiency generation of circularly polarized light via symmetry-induced anomalous reflection. Phys Rev B, 91, 125421(2015).

[39] LL Huang, XZ Chen, H Mühlenbernd et al. Dispersionless phase discontinuities for controlling light propagation. Nano Lett, 12, 5750-5755(2012).

[40] SW Moon, C Lee, Y Yang et al. Tutorial on metalenses for advanced flat optics: design, fabrication, and critical considerations. J Appl Phys, 131, 091101(2022).

[41] WJ Luo, SL Sun, HX Xu et al. Transmissive ultrathin pancharatnam-berry metasurfaces with nearly 100% efficiency. Phys Rev Appl, 7, 044033(2017).

[42] X Fu, HW Liang, JT Li. Metalenses: from design principles to functional applications. Front Optoelectron, 14, 170-186(2021).

[43] J Kim, YM Li, MN Miskiewicz et al. Fabrication of ideal geometric-phase holograms with arbitrary wavefronts. Optica, 2, 958-964(2015).

[44] DD Wen, FY Yue, GX Li et al. Helicity multiplexed broadband metasurface holograms. Nat Commun, 6, 8241(2015).

[45] WT Chen, M Khorasaninejad, AY Zhu et al. Generation of wavelength-independent subwavelength Bessel beams using metasurfaces. Light Sci Appl, 6, e16259(2017).

[46] R Xu, P Chen, J Tang et al. Perfect higher-order Poincaré sphere beams from digitalized geometric phases. Phys Rev Appl, 10, 034061(2018).

[47] D Jeon, K Shin, SW Moon et al. Recent advancements of metalenses for functional imaging. Nano Converg, 10, 24(2023).

[48] MK Liu, DY Choi. Extreme Huygens’ metasurfaces based on quasi-bound states in the continuum. Nano Lett, 18, 8062-8069(2018).

[49] G Kim, Y Kim, J Yun et al. Metasurface-driven full-space structured light for three-dimensional imaging. Nat Commun, 13, 5920(2022).

[50] YJ Wang, QM Chen, WH Yang et al. High-efficiency broadband achromatic metalens for near-IR biological imaging window. Nat Commun, 12, 5560(2021).

[51] WT Chen, AY Zhu, J Sisler et al. A broadband achromatic polarization-insensitive metalens consisting of anisotropic nanostructures. Nat Commun, 10, 355(2019).

[52] JT Heiden, MS Jang. Design framework for polarization-insensitive multifunctional achromatic metalenses. Nanophotonics, 11, 583-591(2022).

[53] M Faraji-Dana, E Arbabi, A Arbabi et al. Compact folded metasurface spectrometer. Nat Commun, 9, 4196(2018).

[54] GY Cai, YH Li, Y Zhang et al. Compact angle-resolved metasurface spectrometer. Nat Mater, 23, 71-78(2024).

[55] RX Wang, MA Ansari, H Ahmed et al. Compact multi-foci metalens spectrometer. Light Sci Appl, 12, 103(2023).

[56] M Faraji-Dana, E Arbabi, A Arbabi et al. Folded planar metasurface spectrometer, 1-2(2018).

[58] F Miyamaru, H Morita, Y Nishiyama et al. Ultrafast optical control of group delay of narrow-band terahertz waves. Sci Rep, 4, 4346(2014).

[59] L Jiang, XZ Li, QX Wu et al. Neural network enabled metasurface design for phase manipulation. Opt Express, 29, 2521-2528(2021).

[60] MZ Chen, Q Cheng, F Xia et al. Metasurface‐based spatial phasers for analogue signal processing. Adv Opt Mater, 8, 2000128(2020).

[61] O Tsilipakos, T Koschny, CM Soukoulis. Antimatched electromagnetic metasurfaces for broadband arbitrary phase manipulation in reflection. ACS Photonics, 5, 1101-1107(2018).

[62] MK Trubetskov, Pechmann M Von, IB Angelov et al. Measurements of the group delay and the group delay dispersion with resonance scanning interferometer. Opt Express, 21, 6658-6669(2013).

[63] NT Song, NX Xu, DZ Shan et al. Broadband achromatic metasurfaces for longwave infrared applications. Nanomaterials, 11, 2760(2021).

[64] YL He, BX Song, J Tang. Optical metalenses: fundamentals, dispersion manipulation, and applications. Front Optoelectron, 15, 24(2022).

[65] Y Pan, S Neuss, A Leifert et al. Size‐dependent cytotoxicity of gold nanoparticles. Small, 3, 1941-1949(2007).

[66] MR Gonçalves, H Minassian, A Melikyan. Plasmonic resonators: fundamental properties and applications. J Phys D Appl Phys, 53, 443002(2020).

[67] Q Xu, XQ Zhang, YH Xu et al. Plasmonic metalens based on coupled resonators for focusing of surface plasmons. Sci Rep, 6, 37861(2016).

[68] M Autore, R Hillenbrand. What momentum mismatch. Nat Nanotechnol, 14, 308-309(2019).

[69] K Kim, Y Oh, K Ma et al. Plasmon-enhanced total-internal-reflection fluorescence by momentum-mismatched surface nanostructures. Opt Lett, 34, 3905-3907(2009).

[70] LS Qin, X Chen, LL Zhang et al. Design, fabrication and testing of gain SPR sensor chip. J Phys Conf Ser, 1209, 012006(2019).

[71] E Petryayeva, UJ Krull. Localized surface plasmon resonance: nanostructures, bioassays and biosensing—A review. Anal Chim Acta, 706, 8-24(2011).

[72] G Palermo, A Lininger, A Guglielmelli et al. All-optical tunability of metalenses permeated with liquid crystals. ACS nano, 16, 16539-16548(2022).

[73] S Park, JW Hahn, JY Lee. Doubly resonant metallic nanostructure for high conversion efficiency of second harmonic generation. Opt Express, 20, 4856-4870(2012).

[74] C Damgaard-Carstensen, F Ding, C Meng et al. Demonstration of> 2π reflection phase range in optical metasurfaces based on detuned gap-surface plasmon resonators. Sci Rep, 10, 19031(2020).

[75] K Yao, YM Liu. Plasmonic metamaterials. Nanotechnol Rev, 3, 177-210(2014).

[76] XC Tong. Plasmonic metamaterials and metasurfaces. Functional Metamaterials and Metadevices, 129-153(2018).

[77] P Christopher, HL Xin, S Linic. Visible-light-enhanced catalytic oxidation reactions on plasmonic silver nanostructures. Nat Chem, 3, 467-472(2011).

[78] ES Barnard, JS White, A Chandran et al. Spectral properties of plasmonic resonator antennas. Opt Express, 16, 16529-16537(2008).

[79] SL Sun, Q He, JM Hao et al. Electromagnetic metasurfaces: physics and applications. Adv Opt Photonics, 11, 380-479(2019).

[80] A Pors, O Albrektsen, IP Radko et al. Gap plasmon-based metasurfaces for total control of reflected light. Sci Rep, 3, 2155(2013).

[81] F Ding, YQ Yang, RA Deshpande et al. A review of gap-surface plasmon metasurfaces: fundamentals and applications. Nanophotonics, 7, 1129-1156(2018).

[82] A Pors, SI Bozhevolnyi. Plasmonic metasurfaces for efficient phase control in reflection. Opt Express, 21, 27438-27451(2013).

[83] A Pors, MG Nielsen, RL Eriksen et al. Broadband focusing flat mirrors based on plasmonic gradient metasurfaces. Nano Lett, 13, 829-834(2013).

[84] S Boroviks, RA Deshpande, NA Mortensen et al. Multifunctional metamirror: polarization splitting and focusing. ACS Photonics, 5, 1648-1653(2018).

[85] E Cortés, FJ Wendisch, L Sortino et al. Optical metasurfaces for energy conversion. Chem Rev, 122, 15082-15176(2022).

[86] S Linic, P Christopher, DB Ingram. Plasmonic-metal nanostructures for efficient conversion of solar to chemical energy. Nat Mater, 10, 911-921(2011).

[87] P Gutruf, CJ Zou, W Withayachumnankul et al. Mechanically tunable dielectric resonator metasurfaces at visible frequencies. Acs Nano, 10, 133-141(2016).

[88] S Campione, LI Basilio, LK Warne et al. Tailoring dielectric resonator geometries for directional scattering and Huygens’ metasurfaces. Opt Express, 23, 2293-2307(2015).

[89] M Decker, I Staude, M Falkner et al. High‐efficiency dielectric Huygens’ surfaces. Adv Opt Mater, 3, 813-820(2015).

[90] SA Maier. Plasmonics: Fundamentals and Applications(2007).

[91] K Koshelev, Y Kivshar. Dielectric resonant metaphotonics. ACS Photonics, 8, 102-112(2021).

[92] DM Lin, PY Fan, E Hasman et al. Dielectric gradient metasurface optical elements. Science, 345, 298-302(2014).

[93] RC Devlin, M Khorasaninejad, WT Chen et al. Broadband high-efficiency dielectric metasurfaces for the visible spectrum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 113, 10473-10478(2016).

[94] SH Zhou, ZX Shen, XA Li et al. Liquid crystal integrated metalens with dynamic focusing property. Opt Lett, 45, 4324-4327(2020).

[95] MY Pan, YF Fu, MJ Zheng et al. Dielectric metalens for miniaturized imaging systems: progress and challenges. Light Sci Appl, 11, 195(2022).

[96] M Kerker, DS Wang, CL Giles. Electromagnetic scattering by magnetic spheres. J Opt Soc Am, 73, 765-767(1983).

[97] MM Bukharin, VY Pecherkin, AK Ospanova et al. Transverse Kerker effect in all-dielectric spheroidal particles. Sci Rep, 12, 7997(2022).

[98] W Liu, YS Kivshar. Generalized Kerker effects in nanophotonics and meta-optics [Invited]. Opt Express, 26, 13085-13105(2018).

[99] WW Liu, ZC Li, H Cheng et al. Dielectric resonance-based optical metasurfaces: from fundamentals to applications. iScience, 23, 101868(2020).

[100] P Genevet, F Capasso, F Aieta et al. Recent advances in planar optics: from plasmonic to dielectric metasurfaces. Optica, 4, 139-152(2017).

[101] S Long, M McAllister, L Shen. The resonant cylindrical dielectric cavity antenna. IEEE Trans Antennas Propag, 31, 406-412(1983).

[102] SW Wang, JJ Lai, T Wu et al. Wide-band achromatic metalens for visible light by dispersion compensation method. J Phys D Appl Phys, 50, 455101(2017).

[103] S Rytov. Electromagnetic properties of a finely stratified medium. Sov Phys JEPT, 2, 466-475(1956).

[104] S Vo, D Fattal, WV Sorin et al. Sub-wavelength grating lenses with a twist. IEEE Photonics Technol Lett, 26, 1375-1378(2014).

[105] A Arbabi, Y Horie, AJ Ball et al. Subwavelength-thick lenses with high numerical apertures and large efficiency based on high-contrast transmitarrays. Nat Commun, 6, 7069(2015).

[106] DA Powell. Interference between the modes of an all-dielectric meta-atom. Phys Rev Appl, 7, 034006(2017).

[107] Q Wang, ETF Rogers, B Gholipour et al. Optically reconfigurable metasurfaces and photonic devices based on phase change materials. Nat Photonics, 10, 60-65(2016).

[108] YF Zhang, C Fowler, JH Liang et al. Electrically reconfigurable non-volatile metasurface using low-loss optical phase-change material. Nat Nanotechnol, 16, 661-666(2021).

[109] S Abdollahramezani, O Hemmatyar, M Taghinejad et al. Electrically driven reprogrammable phase-change metasurface reaching 80% efficiency. Nat Commun, 13, 1696(2022).

[110] Y Wang, DJ Cui, Y Wang et al. Electrically and thermally tunable multifunctional terahertz metasurface array. Phys Rev A, 105, 033520(2022).

[111] ZW Shao, X Cao, HJ Luo et al. Recent progress in the phase-transition mechanism and modulation of vanadium dioxide materials. NPG Asia Mater, 10, 581-605(2018).

[112] MY Shalaginov, SS An, YF Zhang et al. Reconfigurable all-dielectric metalens with diffraction-limited performance. Nat Commun, 12, 1225(2021).

[113] WH Zhang, XQ Wu, L Li et al. Fabrication of a VO2-based tunable metasurface by electric-field scanning probe lithography with precise depth control. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, 15, 13517-13525(2023).

[114] MRM Hashemi, SH Yang, TY Wang et al. Electronically-controlled beam-steering through vanadium dioxide metasurfaces. Sci Rep, 6, 35439(2016).

[115] J King, CH Wan, TJ Park et al. Electrically tunable VO2–metal metasurface for mid-infrared switching, limiting and nonlinear isolation. Nat Photonics, 18, 74-80(2024).

[116] CH Wan, Z Zhang, D Woolf et al. On the optical properties of thin‐film vanadium dioxide from the visible to the far infrared. Ann Phys, 531, 1900188(2019).

[117] F Chu, LL Tian, R Li et al. Adaptive nematic liquid crystal lens array with resistive layer. Liq Cryst, 47, 563-571(2020).

[118] DH Kang, HS Heo, YH Yang et al. Liquid crystal-integrated metasurfaces for an active photonic platform. Opto-Electron Adv, 7, 230216(2024).

[119] X Chang, M Pivnenko, P Shrestha et al. Electrically tuned active metasurface towards metasurface-integrated liquid crystal on silicon (meta-LCoS) devices. Opt Express, 31, 5378-5387(2023).

[120] YY Ji, F Fan, X Zhang et al. Active terahertz anisotropy and dispersion engineering based on dual-frequency liquid crystal and dielectric metasurface. J Lightwave Technol, 38, 4030-4036(2020).

[121] D Rocco, L Carletti, R Caputo et al. Switching the second harmonic generation by a dielectric metasurface via tunable liquid crystal. Opt Express, 28, 12037-12046(2020).

[122] T Badloe, Y Kim, J Kim et al. Bright-field and edge-enhanced imaging using an electrically tunable dual-mode metalens. ACS Nano, 17, 14678-14685(2023).

[123] M Bosch, MR Shcherbakov, K Won et al. Electrically actuated varifocal lens based on liquid-crystal-embedded dielectric metasurfaces. Nano Lett, 21, 3849-3856(2021).

[124] SM Kamali, A Arbabi, E Arbabi et al. Decoupling optical function and geometrical form using conformal flexible dielectric metasurfaces. Nat Commun, 7, 11618(2016).

[125] SM Kamali, E Arbabi, A Arbabi et al. Highly tunable elastic dielectric metasurface lenses. Laser Photonics Rev, 10, 1002-1008(2016).

[126] J Li, HJ Fan, H Ye et al. Design of multifunctional tunable metasurface assisted by elastic substrate. Nanomaterials, 12, 2387(2022).

[127] WL Li, P He, DY Lei et al. Super-resolution multicolor fluorescence microscopy enabled by an apochromatic super-oscillatory lens with extended depth-of-focus. Nat Commun, 14, 5107(2023).

[128] YX Ren, HS He, HJ Tang et al. Non-diffracting light wave: fundamentals and biomedical applications. Front Phys, 9, 698343(2021).

[129] Z Bouchal. Nondiffracting optical beams: physical properties, experiments, and applications. Czech J Phys, 53, 537-578(2003).

[130] DC Li, XR Wang, JZ Ling et al. Planar efficient metasurface for generation of Bessel beam and super-resolution focusing. Opt Quant Electron, 53, 143(2021).

[131] ZM Lin, XW Li, RZ Zhao et al. High-efficiency Bessel beam array generation by Huygens metasurfaces. Nanophotonics, 8, 1079-1085(2019).

[132] FH Shi, M Qiu, L Zhang et al. Multiplane illumination enabled by Fourier-transform metasurfaces for high-speed light-sheet microscopy. ACS Photonics, 5, 1676-1684(2018).

[133] CS Li, YH Guo, XZ Chang et al. A metasurface-on-fiber light-sheet generator for biological imaging. Opt Commun, 559, 130378(2024).

[134] Y Luo, ML Tseng, S Vyas et al. Metasurface‐based abrupt autofocusing beam for biomedical applications. Small Methods, 6, 2101228(2022).

[135] RW Lu, YJ Liang, GH Meng et al. Rapid mesoscale volumetric imaging of neural activity with synaptic resolution. Nat Methods, 17, 291-294(2020).

[136] XW Wang, ZQ Nie, Y Liang et al. Recent advances on optical vortex generation. Nanophotonics, 7, 1533-1556(2018).

[137] S Wang, L Li, S Wen et al. Metalens for accelerated optoelectronic edge detection under ambient illumination. Nano Lett, 24, 356-361(2023).

[138] NI Zheludev. What diffraction limit. Nat Mater, 7, 420-422(2008).

[139] P Hänninen. Beyond the diffraction limit. Nature, 419, 802(2002).

[140] SC Park, MK Park, MG Kang. Super-resolution image reconstruction: a technical overview. IEEE Signal Process Mag, 20, 21-36(2003).

[141] B Huang, H Babcock, XW Zhuang. Breaking the diffraction barrier: super-resolution imaging of cells. Cell, 143, 1047-1058(2010).

[142] KY Bliokh, AY Bekshaev, F Nori. Extraordinary momentum and spin in evanescent waves. Nat Commun, 5, 3300(2014).

[143] D Loerke, B Preitz, W Stuhmer et al. Super-resolution measurements with evanescent-wave fluorescence-excitation using variable beam incidence. J Biomed Opt, 5, 23-30(2000).

[144] JB Pendry. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys Rev Lett, 85, 3966-3969(2000).

[145] N Fang, H Lee, C Sun et al. Sub-diffraction-limited optical imaging with a silver superlens. Science, 308, 534-537(2005).

[146] D Lu, ZW Liu. Hyperlenses and metalenses for far-field super-resolution imaging. Nat Commun, 3, 1205(2012).

[147] M Kim, S So, K Yao et al. Deep sub-wavelength nanofocusing of UV-visible light by hyperbolic metamaterials. Sci Rep, 6, 38645(2016).

[148] Z Jacob, LV Alekseyev, E Narimanov. Optical hyperlens: far-field imaging beyond the diffraction limit. Opt Express, 14, 8247-8256(2006).

[149] ZW Liu, H Lee, Y Xiong et al. Far-field optical hyperlens magnifying sub-diffraction-limited objects. Science, 315, 1686(2007).

[150] L Kastrup, H Blom, C Eggeling et al. Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy in subdiffraction focal volumes. Phys Rev Lett, 94, 178104(2005).

[151] A Honigmann, V Mueller, H Ta et al. Scanning STED-FCS reveals spatiotemporal heterogeneity of lipid interaction in the plasma membrane of living cells. Nat Commun, 5, 5412(2014).

[152] A Barulin, I Kim. Hyperlens for capturing sub-diffraction nanoscale single molecule dynamics. Opt Express, 31, 12162-12174(2023).

[153] FF Wei, JL Ponsetto, ZW Liu. Plasmonic structured illumination microscopy. Plasmonics and Super-Resolution Imaging, 127-163(2017).

[154] FF Wei, D Lu, H Shen et al. Wide field super-resolution surface imaging through plasmonic structured illumination microscopy. Nano Lett, 14, 4634-4639(2014).

[155] SB Wei, T Lei, LP Du et al. Sub-100nm resolution PSIM by utilizing modified optical vortices with fractional topological charges for precise phase shifting. Opt Express, 23, 30143-30148(2015).

[156] JL Ponsetto, FF Wei, ZW Liu. Localized plasmon assisted structured illumination microscopy for wide-field high-speed dispersion-independent super resolution imaging. Nanoscale, 6, 5807-5812(2014).

[157] JL Ponsetto, A Bezryadina, FF Wei et al. Experimental demonstration of localized plasmonic structured illumination microscopy. ACS Nano, 11, 5344-5350(2017).

[158] YU Lee, SL Li, GBM Wisna et al. Hyperbolic material enhanced scattering nanoscopy for label-free super-resolution imaging. Nat Commun, 13, 6631(2022).

[159] ETF Rogers, J Lindberg, T Roy et al. A super-oscillatory lens optical microscope for subwavelength imaging. Nat Mater, 11, 432-435(2012).

[160] MV Berry, S Popescu. Evolution of quantum superoscillations and optical superresolution without evanescent waves. J Phys A: Math Gen, 39, 6965-6977(2006).

[161] Y Aharonov, DZ Albert, L Vaidman. How the result of a measurement of a component of the spin of a spin-1/2 particle can turn out to be 100. Phys Rev Lett, 60, 1351-1354(1988).

[162] FM Huang, N Zheludev, YF Chen et al. Focusing of light by a nanohole array. Appl Phys Lett, 90, 091119(2007).

[163] NI Zheludev, G Yuan. Optical superoscillation technologies beyond the diffraction limit. Nat Rev Phys, 4, 16-32(2022).

[164] G Chen, ZQ Wen, CW Qiu. Superoscillation: from physics to optical applications. Light Sci Appl, 8, 56(2019).

[165] F Qin, K Huang, JF Wu et al. A supercritical lens optical label‐free microscopy: sub‐diffraction resolution and ultra‐long working distance. Adv Mater, 29, 1602721(2017).

[166] Z Li, T Zhang, YQ Wang et al. Achromatic Broadband super‐resolution imaging by super‐oscillatory metasurface. Laser Photonics Rev, 12, 1800064(2018).

[167] GH Yuan, ETF Rogers, NI Zheludev. Achromatic super-oscillatory lenses with sub-wavelength focusing. Light Sci Appl, 6, e17036(2017).

[168] ETF Rogers, S Savo, J Lindberg et al. Super-oscillatory optical needle. Appl Phys Lett, 102, 031108(2013).

[169] T Roy, ETF Rogers, GH Yuan et al. Point spread function of the optical needle super-oscillatory lens. Appl Phys Lett, 104, 231109(2014).

[170] GH Yuan, ETF Rogers, T Roy et al. Planar super-oscillatory lens for sub-diffraction optical needles at violet wavelengths. Sci Rep, 4, 6333(2014).

[171] JS Diao, WZ Yuan, YT Yu et al. Controllable design of super-oscillatory planar lenses for sub-diffraction-limit optical needles. Opt Express, 24, 1924-1933(2016).

[172] G Chen, ZX Wu, AP Yu et al. Planar binary-phase lens for super-oscillatory optical hollow needles. Sci Rep, 7, 4697(2017).

[173] DR Solli, B Jalali. Analog optical computing. Nat Photonics, 9, 704-706(2015).

[174] SS He, RS Wang, HL Luo. Computing metasurfaces for all-optical image processing: a brief review. Nanophotonics, 11, 1083-1108(2022).

[175] J Selinummi, P Ruusuvuori, I Podolsky et al. Bright field microscopy as an alternative to whole cell fluorescence in automated analysis of macrophage images. PLoS One, 4, e7497(2009).

[176] D Marr, E Hildreth. Theory of edge detection. Proc Roy Soc B Biol Sci, 207, 187-217(1980).

[177] J Canny. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell, PAMI-8, 679-698(1986).

[178] R Maini, H Aggarwal. Study and comparison of various image edge detection techniques. Int J Image Process, 3, 1-12(2009).

[179] JK Wang, WH Zhang, QQ Qi et al. Gradual edge enhancement in spiral phase contrast imaging with fractional vortex filters. Sci Rep, 5, 15826(2015).

[180] SB Wei, SW Zhu, XC Yuan. Image edge enhancement in optical microscopy with a Bessel-like amplitude modulated spiral phase filter. J Opt, 13, 105704(2011).

[181] S Yuan, D Xiang, XM Liu et al. Edge detection based on computational ghost imaging with structured illuminations. Opt Commun, 410, 350-355(2018).

[182] Y Zhou, HY Zheng, II Kravchenko et al. Flat optics for image differentiation. Nat Photonics, 14, 316-323(2020).

[183] MK Chen, YF Wu, L Feng et al. Principles, functions, and applications of optical meta‐lens. Adv Opt Mater, 9, 2001414(2021).

[184] S Abdollahramezani, O Hemmatyar, A Adibi. Meta-optics for spatial optical analog computing. Nanophotonics, 9, 4075-4095(2020).

[185] L Wan, DP Pan, SF Yang et al. Optical analog computing of spatial differentiation and edge detection with dielectric metasurfaces. Opt Lett, 45, 2070-2073(2020).

[186] JX Zhou, HL Qian, JX Zhao et al. Two-dimensional optical spatial differentiation and high-contrast imaging. Natl Sci Rev, 8, nwaa176(2021).

[187] C Guo, M Xiao, M Minkov et al. Photonic crystal slab Laplace operator for image differentiation. Optica, 5, 251-256(2018).

[188] Y Kim, GY Lee, J Sung et al. Spiral metalens for phase contrast imaging. Adv Funct Mater, 32, 2106050(2022).

[189] HG Dong, FQ Wang, RS Liang et al. Visible-wavelength metalenses for diffraction-limited focusing of double polarization and vortex beams. Opt Mater Express, 7, 4029-4037(2017).

[190] C Zhou, YJ Chen, Y Li et al. Laplace differentiator based on metasurface with toroidal dipole resonance. Adv Funct Mater, 34, 2313777(2024).

[191] CH Chu, YH Chia, HC Hsu et al. Intelligent phase contrast meta-microscope system. Nano Lett, 23, 11630-11637(2023).

[192] A Overvig, A Alù. Diffractive nonlocal metasurfaces. Laser Photonics Rev, 16, 2100633(2022).

[193] K Shastri, F Monticone. Nonlocal flat optics. Nat Photonics, 17, 36-47(2023).

[194] M Kim, D Lee, J Kim et al. Nonlocal metasurfaces‐enabled analog light localization for imaging and lithography. Laser Photonics Rev, 18, 2300718(2024).

[195] Shiyu Li,, Wei Hsu Chia. Thickness bound for nonlocal wide-field-of-view metalenses. Light: Science & Applications, 11.1, 338(2022).

[196] H Kwon, D Sounas, A Cordaro et al. Nonlocal metasurfaces for optical signal processing. Phys Rev Lett, 121, 173004(2018).

[197] H Kwon, A Cordaro, D Sounas et al. Dual-polarization analog 2D image processing with nonlocal metasurfaces. ACS Photonics, 7, 1799-1805(2020).

[198] MR Arnison, KG Larkin, CJR Sheppard et al. Linear phase imaging using differential interference contrast microscopy. J Microsc, 214, 7-12(2004).

[199] F Zernike. How I discovered phase contrast. Science, 121, 345-349(1955).

[200] C Preza, DL Snyder, JA Conchello. Theoretical development and experimental evaluation of imaging models for differential-interference-contrast microscopy. J Opt Soc Am A, 16, 2185-2199(1999).

[201] C Preza. Rotational-diversity phase estimation from differential-interference-contrast microscopy images. J Opt Soc Am A, 17, 415-424(2000).

[202] M Shribak. Quantitative orientation-independent differential interference contrast microscope with fast switching shear direction and bias modulation. J Opt Soc Am A, 30, 769-782(2013).

[203] Q Zhao, L Kang, B Du et al. Electrically tunable negative permeability metamaterials based on nematic liquid crystals. Appl Phys Lett, 90, 011112(2007).

[204] B Kang, JH Woo, E Choi et al. Optical switching of near infrared light transmission in metamaterial-liquid crystal cell structure. Opt Express, 18, 16492-16498(2010).

[205] FL Zhang, WH Zhang, Q Zhao et al. Electrically controllable fishnet metamaterial based on nematic liquid crystal. Opt Express, 19, 1563-1568(2011).

[206] H Su, H Wang, H Zhao et al. Liquid-crystal-based electrically tuned electromagnetically induced transparency metasurface switch. Sci Rep, 7, 17378(2017).

[207] P Yu, JX Li, N Liu. Electrically tunable optical metasurfaces for dynamic polarization conversion. Nano Lett, 21, 6690-6695(2021).

[208] T Badloe, I Kim, Y Kim et al. Electrically tunable bifocal metalens with diffraction‐limited focusing and imaging at visible wavelengths. Adv Sci, 8, 2102646(2021).

[209] SL Zhou, YF Wu, SR Chen et al. Phase change induced active metasurface devices for dynamic wavefront control. J Phys D Appl Phys, 53, 204001(2020).

[210] HS Ee, R Agarwal. Tunable metasurface and flat optical zoom lens on a stretchable substrate. Nano Lett, 16, 2818-2823(2016).

[211] ML Tseng, HH Hsiao, CH Chu et al. Metalenses: advances and applications. Adv Opt Mater, 6, 1800554(2018).

[212] CA Dirdal, PCV Thrane, FT Dullo et al. MEMS-tunable dielectric metasurface lens using thin-film PZT for large displacements at low voltages. Opt Lett, 47, 1049-1052(2022).

[213] ZY Han, S Colburn, A Majumdar et al. MEMS-actuated metasurface Alvarez lens. Microsystems, 6, 79(2020).

[214] E Arbabi, A Arbabi, SM Kamali et al. MEMS-tunable dielectric metasurface lens. Nat Commun, 9, 812(2018).

[215] Y Luo, CH Chu, S Vyas et al. Varifocal metalens for optical sectioning fluorescence microscopy. Nano Lett, 21, 5133-5142(2021).

[216] Y Kim, PC Wu, R Sokhoyan et al. Phase modulation with electrically tunable vanadium dioxide phase-change metasurfaces. Nano Lett, 19, 3961-3968(2019).

[217] W Bai, P Yang, J Huang et al. Near-infrared tunable metalens based on phase change material Ge2Sb2Te5. Sci Rep, 9, 5368(2019).

[218] A Afridi, J Gieseler, N Meyer et al. Ultrathin tunable optomechanical metalens. Nano Lett, 23, 2496-2501(2023).

[219] YK Song, WC Liu, XL Wang et al. Multifunctional metasurface lens with tunable focus based on phase transition material. Front Phys, 9, 651898(2021).

[220] B Crosson, A Ford, KM McGregor et al. Functional imaging and related techniques: an introduction for rehabilitation researchers. J Rehabil Res Dev, 47, vii-xxxiv(2010).

[221] J Tsao. Ultrafast imaging: principles, pitfalls, solutions, and applications. J Magn Reson Imaging, 32, 252-266(2010).

[222] E Sezgin, F Schneider, S Galiani et al. Measuring nanoscale diffusion dynamics in cellular membranes with super-resolution STED–FCS. Nat Protoc, 14, 1054-1083(2019).

[223] L Schermelleh, A Ferrand, T Huser et al. Super-resolution microscopy demystified. Nat Cell Biol, 21, 72-84(2019).

[224] AV Kuhlmann, J Houel, D Brunner et al. A dark-field microscope for background-free detection of resonance fluorescence from single semiconductor quantum dots operating in a set-and-forget mode. Rev Sci Instrum, 84, 073905(2013).

[225] P Beard. Biomedical photoacoustic imaging. Interface Focus, 1, 602-631(2011).

[226] V Balasubramani, A Kuś, HY Tu et al. Holographic tomography: techniques and biomedical applications [Invited]. Appl Opt, 60, B65-B80(2021).

[227] H Wang, T Akkin, C Magnain et al. Polarization sensitive optical coherence microscopy for brain imaging. Opt Lett, 41, 2213-2216(2016).

[228] B Baumann. Polarization sensitive optical coherence tomography: a review of technology and applications. Appl Sci, 7, 474(2017).

[229] JM Girkin, MT Carvalho. The light-sheet microscopy revolution. J Opt, 20, 053002(2018).

[230] BC Chen, WR Legant, K Wang et al. Lattice light-sheet microscopy: imaging molecules to embryos at high spatiotemporal resolution. Science, 346, 1257998(2014).

[231] EHK Stelzer, F Strobl, BJ Chang et al. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy. Nat Rev Methods Primers, 1, 73(2021).

[233] E Arbabi, JQ Li, RJ Hutchins et al. Two-photon microscopy with a double-wavelength metasurface objective lens. Nano Lett, 18, 4943-4948(2018).

[234] ML Rynes, DA Surinach, S Linn et al. Miniaturized head-mounted microscope for whole-cortex mesoscale imaging in freely behaving mice. Nat Methods, 18, 417-425(2021).

[235] J Yao, R Lin, MK Chen et al. Integrated-resonant metadevices: a review. Adv Photonics, 5, 024001(2023).

[236] S Colburn, AL Zhan, A Majumdar. Metasurface optics for full-color computational imaging. Sci Adv, 4, eaar2114(2018).

[237] O Avayu, E Almeida, Y Prior et al. Composite functional metasurfaces for multispectral achromatic optics. Nat Commun, 8, 14992(2017).

[238] X Hua, YJ Wang, SM Wang et al. Ultra-compact snapshot spectral light-field imaging. Nat Commun, 13, 2732(2022).

[239] E Tseng, S Colburn, J Whitehead et al. Neural nano-optics for high-quality thin lens imaging. Nat Commun, 12, 6493(2021).

[240] P Chakravarthula, JP Sun, X Li et al. Thin on-sensor nanophotonic array cameras. ACM Trans Graph, 42, 249(2023).

[241] B Park, D Oh, J Kim et al. Functional photoacoustic imaging: from nano- and micro- to macro-scale. Nano Converg, 10, 29(2023).

[242] B Park, KM Lee, S Park et al. Deep tissue photoacoustic imaging of nickel(II) dithiolene-containing polymeric nanoparticles in the second near-infrared window. Theranostics, 10, 2509-2521(2020).

[243] DP Wang, YH Wang, WR Wang et al. Deep tissue photoacoustic computed tomography with a fast and compact laser system. Biomed Opt Express, 8, 112-123(2017).

[244] YT Zhao, CK Guo, YQ Zhang et al. Ultraviolet metalens for photoacoustic microscopy with an elongated depth of focus. Opt Lett, 48, 3435-3438(2023).

[245] DW Li, L Humayun, E Vienneau et al. Seeing through the skin: photoacoustic tomography of skin vasculature and beyond. JID innov, 1, 100039(2021).

[246] JJ Yao, LV Wang. Sensitivity of photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics, 2, 87-101(2014).

[247] WW Liu, PC Li. Photoacoustic imaging of cells in a three-dimensional microenvironment. J Biomed Sci, 27, 3(2020).

[248] YZ Liang, WB Fu, Q Li et al. Optical-resolution functional gastrointestinal photoacoustic endoscopy based on optical heterodyne detection of ultrasound. Nat Commun, 13, 7604(2022).

[249] GJ Tearney, SA Boppart, BE Bouma et al. Scanning single-mode fiber optic catheter–endoscope for optical coherence tomography: erratum. Opt Lett, 21, 912(1996).

[250] GJ Tearney, ME Brezinski, BE Bouma et al. In vivo endoscopic optical biopsy with optical coherence tomography. Science, 276, 2037-2039(1997).

[251] LP Hariri, DC Adams, JC Wain et al. Endobronchial optical coherence tomography for low-risk microscopic assessment and diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in vivo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 197, 949-952(2018).

[252] JY Yang, I Ghimire, PC Wu et al. Photonic crystal fiber metalens. Nanophotonics, 8, 443-449(2019).

[253] W Drexler. Ultrahigh-resolution optical coherence tomography. J Biomed Opt, 9, 47-74(2004).

[254] S Aumann, S Donner, J Fischer et al. Optical coherence tomography (OCT): principle and technical realization.. High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology: New Frontiers in Biomedical Optics, 59-85(2019).

[255] QC Zhao, WH Yuan, JQ Qu et al. Optical fiber-integrated metasurfaces: an emerging platform for multiple optical applications. Nanomaterials (Basel), 12(2022).

[256] M Pahlevaninezhad, YW Huang, M Pahlevani et al. Metasurface-based bijective illumination collection imaging provides high-resolution tomography in three dimensions. Nat Photonics, 16, 203-211(2022).

[257] JE Fröch, LC Huang, QAA Tanguy et al. Real time full-color imaging in a meta-optical fiber endoscope. eLight, 3, 13(2023).

[258] LP Hariri, M Villiger, MB Applegate et al. Seeing beyond the bronchoscope to increase the diagnostic yield of bronchoscopic biopsy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 187, 125-129(2013).

[259] DC Adams, LP Hariri, AJ Miller et al. Birefringence microscopy platform for assessing airway smooth muscle structure and function in vivo. Sci Transl Med, 8, 359ra131(2016).

[260] SK Nadkarni, MC Pierce, BH Park et al. Measurement of collagen and smooth muscle cell content in atherosclerotic plaques using polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol, 49, 1474-1481(2007).

[261] YH Chia, WH Liao, S Vyas et al. In vivo intelligent fluorescence endo‐microscopy by varifocal meta‐device and deep learning. Adv Sci, 11, 2307837(2024).

[262] CH Chu, S Vyas, Y Luo et al. Recent developments in biomedical applications of metasurface optics. APL Photonics, 9, 030901(2024).

[263] J Gupta, P Das, R Bhattacharjee et al. Enhancing signal-to-noise ratio of clinical 1.5T MRI using metasurface-inspired flexible wraps. Appl Phys A, 129, 725(2023).

[264] MA Brown, RC Semelka. MRI: Basic Principles and Applications(2011).

[265] DB Plewes, W Kucharczyk. Physics of MRI: a primer. J Magn Reson Imaging, 35, 1038-1054(2012).

[266] Reeth E Van, IWK Tham, CH Tan et al. Super‐resolution in magnetic resonance imaging: a review. Concepts Magn Reson Part A, 40, 306-325(2012).

[267] EH Voormolen, SJH Diederen, P Woerdeman et al. Implications of extracranial distortion in ultra-high-field magnetic resonance imaging for image-guided cranial neurosurgery. World Neurosurg, 126, e250-e258(2019).

[268] ZP Li, X Tian, CW Qiu et al. Metasurfaces for bioelectronics and healthcare. Nat Electron, 4, 382-391(2021).

[269] AP Slobozhanyuk, AN Poddubny, AJE Raaijmakers et al. Enhancement of magnetic resonance imaging with metasurfaces. Adv Mater, 28, 1832-1838(2016).

[270] E Stoja, S Konstandin, D Philipp et al. Improving magnetic resonance imaging with smart and thin metasurfaces. Sci Rep, 11, 16179(2021).

[271] EI Kretov, AV Shchelokova, AP Slobozhanyuk. Impact of wire metasurface eigenmode on the sensitivity enhancement of MRI system. Appl Phys Lett, 112, 033501(2018).

[272] XG Zhao, GW Duan, K Wu et al. Intelligent metamaterials based on nonlinearity for magnetic resonance imaging. Adv Mater, 31, 1905461(2019).

[273] CA Corneanu, MO Simón, JF Cohn et al. Survey on RGB, 3D, thermal, and multimodal approaches for facial expression recognition: History, trends, and affect-related applications. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal, 38, 1548-1568(2016).

[275] F Tsalakanidou, S Malassiotis. Real-time 2D+ 3D facial action and expression recognition. Pattern Recognit, 43, 1763-1775(2010).

[276] LF Sun, ZR Wang, JB Jiang et al. In-sensor reservoir computing for language learning via two-dimensional memristors. Sci Adv, 7, eabg1455(2021).

[277] JM Kwon, SP Yang, KH Jeong. Stereoscopic facial imaging for pain assessment using rotational offset microlens arrays based structured illumination. Micro Nano Syst Lett, 9, 11(2021).

[278] H Imaoka, H Hashimoto, K Takahashi et al. The future of biometrics technology: from face recognition to related applications. APSIPA Trans Signal Inf Process, 10, e9(2021).

[279] Jr JD Woodward, C Horn, J Gatune et al. Biometrics: A Look at Facial Recognition(2003).

[280] MY Du. Mobile payment recognition technology based on face detection algorithm. Concurr Comput Pract Exper, 30, e4655(2018).

[281] ZL Li, Q Dai, MQ Mehmood et al. Full-space cloud of random points with a scrambling metasurface. Light Sci Appl, 7, 63(2018).

[282] YY Xie, PN Ni, QH Wang et al. Metasurface-integrated vertical cavity surface-emitting lasers for programmable directional lasing emissions. Nat Nanotechnol, 15, 125-130(2020).

[283] T Hu, QZ Zhong, NX Li et al. CMOS-compatible a-Si metalenses on a 12-inch glass wafer for fingerprint imaging. Nanophotonics, 9, 823-830(2020).

[284] N Grew. NOTES of the WEEK.

[285] J Galbally, R Haraksim, L Beslay. A study of age and ageing in fingerprint biometrics. IEEE Trans Inf Foren Sec, 14, 1351-1365(2019).

[286] N Yager, A Amin. Fingerprint classification: a review. Pattern Anal Appl, 7, 77-93(2004).

[288] HC Lee, RE Gaensslen. Advances in Fingerprint Technology(2001).

[289] WC Yang, S Wang, JK Hu et al. Security and accuracy of fingerprint-based biometrics: a review. Symmetry, 11, 141(2019).

[291] DK Oh, T Lee, B Ko et al. Nanoimprint lithography for high-throughput fabrication of metasurfaces. Front Optoelectron, 14, 229-251(2021).

Set citation alerts for the article

Please enter your email address

AI Video Guide

AI Video Guide  AI Picture Guide

AI Picture Guide AI One Sentence

AI One Sentence